In Gaza

|

| One of many destroyed water wells in Gaza’s border regions. |

related video

“If we didn’t get the wheat planted today, we would not have had crops this year,” says Abu Saleh Abu Taima, eyeing the two Israeli military jeeps parked along the border fence east of Khan Younis, southern Gaza Strip. Although his land is more than 300 meters away, technically outside of the Israeli-imposed “buffer zone,” Abu Taima has reason to be wary.

“They shot at us yesterday. I was here with my wife and nephews.”

Like many farmers along Gaza’s eastern and northern borders, Abu Taima has been delayed planting by the absence of water and the threat from Israeli soldiers along the border.

“In 1994, we made water lines from Khan Younis, over 10 km away, so that we could irrigate the land. But in winter we rely on the rains, and conserve water in cisterns,” he says.

With most of Gaza’s border region wells, cisterns and water lines destroyed by Israeli forces during last winter’s attacks, farmers have been largely left with no option but to wait for heavier rains.

*destroyed cisterns on Abu Taima land (photos: Rada Daniell)

Years ago, before his land was ravaged by Israeli bulldozers and tanks, Abu Taima grew a variety of melons, fruits, and vegetables. “I had many plum trees, also. Each tree produced 20 boxes of fruit.”

A metal pole on the edge of his 13 dunams [1 dunam is approximate to 1000 square metres] is the only remainder of the large tent he used as shelter from the sun and a place to rest at night. “I used to sleep here, eat here. It was the most relaxing place.”

The extended Abu Taima family owns land east of Khan Younis near and within the buffer zone. “And there are 60 dunams on the other side of the border,” he says, in what is now Israel.

“Israeli soldiers started intensively bulldozing the land in 2003. But they finished the job in the last war on Gaza,” says Hamdan Abu Taima, owner of 30 dunams dangerously close to the buffer zone.

Nasser Abu Taima has 15 dunams of land nearby. Another 15 dunams lie inaccessibly close to the border, rendered off-limits by the Israeli military. “My well was destroyed in the last Israeli war on Gaza. Five years ago I had hothouses for tomatoes, a house here, many trees. It’s all gone. Now I just plant wheat if I can. It’s the simplest.”

Nasser points out the rubble of his home, harvests some ripe cactus fruit and shakes his head. “Such a shame. Such a waste. I knew every inch of this area. Now, I feel sick much of the time because I cannot access my land. And I’ve got 23 in my family to provide for.”

In one 64 dunam area of the Abu Taima region alone, over 1 km from the border and which housed over 100 hothouses, only 2 survived Israeli bulldozing and bombing.

Abu Rayda Abu Taima, seeing farmers on their land near the border, approaches thinking there is coordination with the Israeli authorities. “I’ve got 50 dunams inside the buffer zone which I haven’t accessed in years,” he says, leaving immediately when he learns there is no coordination with Israeli authorities to be on the land, no safety.

Israel imposed the “buffer zone” along Gaza’s side of the internationally-recognized “Green Line” boundary nearly ten years ago. Israeli bulldozers continue to raze decades-old olive and fruit trees, farmland and irrigation piping, and demolish homes, greenhouses, water wells and cisterns, farm machinery and animal shelters.

Extending from Gaza’s most northwestern to southeastern points, the unclearly-marked buffer zone annexes more land than the 300 meters flanking the border. Israeli authorities say anyone found within risks being shot at by Israeli soldiers. At least 13 Palestinian civilians have been killed and 39 injured by Israeli shooting, shelling and aggressions in border regions in and outside of the buffer zone since the 18 January end of Israel’s attacks last year, among them children and women.

A sector destroyed

|

| Farmers in southeastern Gaza take shelter from bullets fired by Israeli soldiers at the border nearly one kilometer away. |

Ahmed Sourani, of the Palestinian Agricultural Relief Committee (PARC), told the Guardian newspaper: “It is indirect confiscation by fear. My fear is that, if it remains, it will become de facto.”

According to PARC, the fertile farmland in and next to the buffer zone was not long ago Gaza’s food basket and half of Gaza’s food needs were produced within the territory.

In 2008, the agricultural sector employed approximately 70,000 farmers, says PARC, including 30,000 farm laborers earning approximately five dollars per day.

One of the most productive industries some years ago, farming now yields the least and has become one of the most dangerous sectors in Gaza, due to Israeli firing, shelling and aggression against people in the border regions.

Of the 175,000 dunams of cultivable land, PARC reports 60 to 75,000 dunams have been destroyed during Israeli invasions and operations. The level of destruction from the last Israeli war on Gaza alone is vast, with 35 to 60 percent of the agricultural industry destroyed, according to the UN and World Health Organization. Gaza’s sole agricultural college, in Beit Hanoun, was also destroyed.

Oxfam notes that the combination of the Israeli war on Gaza and the buffer zone renders around 46 percent of agricultural land useless or unreachable.

More than 35,000 cattle, sheep and goats were killed during the last Israeli attacks, as well as 1 million birds and chickens, according to a United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) September 2009 report.

Even before Israel’s last assault, PARC reported on the grave shortage of agricultural needs due to the Israeli siege on Gaza: “saplings, pesticides and fertilizers, plastic sheets for greenhouses and hoses for irrigation are no longer available,” reads its 2008 report.

A March 2009 OCHA report lists nylon, seeds, olive and fruit tree seedlings, plastic piping and valves, fertilizers, animal feed, livestock and many other items as scarce, many of which are “urgently” needed.

The dearth of agricultural goods, combined with Israel’s policies of destruction and aggression in the buffer zone, has meant that farmers have changed practice completely, planting low-maintenance wheat and rye where vegetables and orchards once flourished, or not planting at all.

Even for farmers whose land lies far from the buffer zone, the banning of agricultural goods and of exports has meant severe losses.

“A few years ago, a box of tomatoes would have sold for 100 shekels. Cucumbers 120 shekels. Now we sell them locally for a tenth of that,” says Jemah*, a farmer in Gaza’s southeast.

In the rows of hothouses on his property, many lie dormant. Those that host cucumbers and tomatoes suffer from the lack of fertilizers and pesticides.

“The leaves should all be green, not discoloured like the majority are. They’re diseased because they need pesticides and because of the poor water quality,” Jemah says.

Water sources were particularly hard hit during Israel’s attack on Gaza last winter.

A UNDP survey following the attacks found that nearly 14,000 dunums of irrigation networks and pipelines have been destroyed, along with 250 wells and 327 water pumps completely damaged, and another 53 wells partially damaged by Israeli bombing and bulldozing. This is excluding the many destroyed cisterns and irrigation ponds.

Farmers now either hand deliver water via plastic jugs or wait for the heavy rains in order to salvage some of their crops. Many others have given up working their land.

|

| Ahmed al-Basiouni: “Now when I water my remaining trees, I do it by hand, tree by tree.” |

Mohammed al-Ibrim, 20, of Benesuhela village near Khan Younis was injured by Israeli shooting in the border region.

“On 18 [correction: 17 February 2009] February 2009, I was working with other farm laborers on land about 500 meters from the border. We’d been working for a couple of hours without problems, and the Israelis had been watching us. Israeli soldiers began shooting from the border as we pushed our pickup truck which had broken down. I was shot in the ankle. There was nothing happening, I don’t know why the Israelis shot at us. We are just trying to earn a living. My 20 shekels per day contributes to support our family of 15.”

His injury came just weeks after cousin Anwar al-Ibrim was martyred by an Israeli soldier’s bullet to the neck. Anwar al-Ibrim leaves behind a wife and two children.

Meanwhile, in Gaza’s north, Ali Hamad, 52, has 18 dunams of land roughly 500 meters from the border east of Beit Hanoun.

“The Israelis bulldozed my citrus trees, water pump, well and irrigation piping in the last war. No one can come here to move the rubble of my well — everyone is afraid of the Israeli soldiers at the border. So now we are just waiting for the winter rains.

All but one well and pump have been destroyed in this region.

“I haven’t watered my few remaining trees since the war. I used to water them once a week, three to four hours per session. Now, they are dehydrated, the lemons and oranges are miniature.”

Mohammed Musleh, 70, lives east of Beit Hanoun, roughly 1.5 kilometers from the border, and owns the only working well and pump in his region.

“There used to be many birds in this area, because it was so fertile, until the Israelis started bulldozing all of the trees, including mine. When people replanted them, the Israelis began destroying the water sources instead.”

Musleh, having lost two tile factories to Israeli bombings over the years, relies on his land for a source of income.

Ahmed al-Basiouni, 53, owned the first well established in the east Beit Hanoun area, built in 1961.

“My brothers and I have 60 dunams of land. Many people took water from our well. It was destroyed in 2003, and again in the last Israeli war. Now when I water my remaining trees, I do it by hand, tree by tree.”

In its September 2009 report, the UNEP warned that Gaza’s aquifer is in “serious danger of collapse,” noting that the problem has roots in the “rise in salt water intrusion from the sea caused by over-extraction of ground water.” According to the report, the salinity and nitrate levels of water are far above WHO-accepted levels. Between 90 and 95 percent of the water available to Palestinians in Gaza is contaminated and hence “unfit for human consumption,” according to WHO standards.

Water has been further contaminated by chemical agents used by the Israeli army during its war on Gaza. More contamination from destroyed asbestos roofing, the toxins produced by the bodies of thousands of animal carcasses, and waste sites which were inaccessible and damaged during and after the attacks on Gaza exacerbates the situation.

Further up the lane, Hassan al-Basiouni, 54, says he has lost a quarter of a million dollars to the Israeli land and well destruction.

“My brothers and I have 41 dunams. Our well was destroyed once before this last war. The materials to make a new well aren’t available in Gaza. The 180 people who earned a living off this land are out of work.”

According to Bassiouni, it costs $200 to raise just one fruit tree to fruit bearing maturity.

“We had 1,500 citrus trees, some destroyed in random Israeli shelling and the rest destroyed during the last Israeli war on Gaza. The few remaining trees are only one year old and produce nothing.”

“This water we’re using,” says Basiouni, referring to the contamination, “actually dehydrates the trees.”

|

| Sena and Amar Mhayssy deliver water by hand after Israel destroyed the water sources on their land. |

In eastern Gaza’s Shejaiye area, Sena, 74, and Amar Mhayssy, 78, are devastated. “Our land has been bulldozed four times. We have nine dunams of land in the buffer zone which we can’t access because the Israelis will shoot at us. We have 10 dunams of land over 500 meters from the border fence. Our olive trees, over 60 years old, were all bulldozed by the Israeli army.”

They persevere in the face of danger and futility.

“Now we’re growing okra and have replanted 40 olive trees. But they will take years before they produce many olives. We need to water the new trees every three days, but our water source was destroyed. So we bring containers to water them. There are 13 people in our family, with four in university. Aside from farming, we have no work.”

Ramzi Hillis is the sole provider for his family of 13.

“In the last war, the Israelis destroyed the irrigation piping, razed all our trees, destroyed our chicken farm, and our well.

Unable to work on the land, Hillis drives a taxi instead, earning an average of 60 shekels per day.

Sabri Jendiya, 74, has farmed his family’s land since he was a child. “We have 30 dunams about 800m from the border fence. Because of the danger from Israeli soldiers’ shooting, I can’t work my land like I used. Our water sources were destroyed by the Israeli war on Gaza. We invested everything in our land, for nothing. There are 30 people in our house and only one of my sons has work.”

Neighbour Shabaan Mhayssy, 78, also lost his cistern and trees to Israeli bulldozers. “I was so happy on my 7.5 dunams. My olive trees were very old. I spent 10,000 shekels to make the water cistern with a pump for watering the land. Now the 25 people in our house have no source of income.”

Zaytoun, eastern Gaza, became well-known for the over 40 martyred Israeli bombing of their residential area. Mousa Samouni, 19, lost many members of his family and their land.

“My parents, Rachad and Rabab, and two brothers were martyred in the Israeli attacks. The Israelis also destroyed our chicken farm and many of our olive and fruit trees. It was such a beautiful place; you could sleep here, so tranquil. I remember exactly where every tree was. Now we have no income.”

In Wadi Salqqa, central eastern Gaza, the land is still moguls of earth torn-up by Israeli bulldozers.

The water tank serving Wadi Salqqa village and part of Deir el Balah city, a total of 150,000 people, was shelled during the Israeli war on Gaza. It was 2 months before the motor could be repaired. The tank has been re-built 4 times over the years following Israeli attacks.

In al-Faraheen village, east of Khan Younis, Jaber Abu Rjila now can only work his land on a small scale.

“My chicken farm — over 500 meters from the border — as well as 500 fruit and olive trees and 100 dunams of wheat and peas of my and my neighbors’ land were destroyed in May 2008 by Israeli bulldozers. My cistern, the pump and motor and one of my tractors were destroyed. The side of our house facing the border is filled with bullet holes from the Israeli soldiers. Now, because of the danger we rent a home half a kilometer away. I’ve lost my income, how can I pay for rent?”

Ahmed Sourani, of PARC, says the way to contest the creeping buffer zone and soaring poverty in Gaza is two-fold: encourage farmers to stay on their land, and encourage urban agriculture.

Groups like PARC, the Union of Agricultural Work Committee (UAWC) and smaller community initiatives work on rehabilitating destroyed farmland, starting small farm plots or projects raising chicken, rabbit, or sheep for impoverished families, and defying Israel’s imposition of the buffer zone.

The UAWC has worked for the past two years in organizing non-violent demonstrations against the buffer zone, encouraging farmers and civilians living near the border to march on their land and call for their rights.

In Gaza’s north, the Beit Hanoun Local Initiative leads weekly non-violent demonstrations up to and within the 300 metre no-go zone.

The Committee for Protection and Developing Agricultural Lands east of Gaza formed recently to contest the continued annexation and destruction of the border regions. Their central goal is in helping farmers return to their land.

“When farmers were producing, we were able to live self-sufficiently and earn money. Now, we are dependent on aid.”

“For the past two years, we haven’t exported our strawberries or carnations,” said Ahmed Al Shafee, of the Agricultural Coooperative in Beit Lahia, northern Gaza. Aside from a paltry amount of flowers allowed out in February 2009, Gaza’s exports have screeched to a halt. “We fed our flowers to animals for the past two seasons, and sold the strawberries on the local market, at a huge loss,” he said. In Europe, strawberries will sell for around 14 shekels per kilo. In Gaza, the Cooperative sold berries at 2 shekels per kilo.

“It costs $3,500 to cultivate one dunam,” says Shafee, “and each dunam produces about 3.5 tons. Before siege, we exported 2,000 tons strawberries annually to Europe.”

“Carnations,” he says, “cost even more to produce: $10,000 for each dunam.”

Many strawberry and flower farmers have started planting less, or have completely changed crops. In 2008, the Agricultural Coop reports 1,500 dunams of strawberries were cultivated, compared to the 2,500 dunams before the siege on Gaza.

“If we don’t export, we will lose revenue and we lose our markets in Europe.”

Since the first constraints of the siege on Gaza were imposed nearly four years ago, the destruction of Gaza’s agricultural sector and potential to provide produce and economy to a severely undernourished Strip has dramatically worsened.

With Palestinians in Gaza now largely dependent on the expensive Israeli produce that is inconsistently allowed into Gaza, the plight of the farmers reverberates throughout the population.

*January 31 2010, Abu Taima, Khoza’a, southeastern Gaza: Israeli military jeep and hummer patrol along the Green Line border. (photo: Rada Daniell)

*February 9 2010, Abu Taima, Khoza’a, southeastern Gaza: Israeli soldiers aim and repeatedly fire upon visibly unarmed Palestinian farmers and international accompaniment. Shots land and pass within less than 10 metres of us. (photo: Rada Daniell)

*February 9 2010, Abu Taima, Khoza’a, southeastern Gaza: Israeli soldier standing in relaxed, unthreatened position between rounds of firing on unarmed Palestinian and international civilians. (photo: Rada Daniell)

*Laetaemat, Khoza’a, east of Khan Younis, 24 January 2010. Israeli automated machine gun tower, open. Israeli soldiers can monitor and shoot from remote booths. (photo: Rada Daniell)

*Laetaemat, Khoza’a, east of Khan Younis, 24 January 2010. Israeli automated machine gun tower, open. Israeli soldiers can monitor and shoot from remote booths. (photo: Rada Daniell)

*Ali Hammad, east Beit Hanoun: land, well, motor destroyed by Israeli soldiers.

*Hassan al Basiouni: land and well in east Beit Hanoundestroyed again by Israeli soldiers.

*Ali Zaneen: his land and well in Beit Hanoun were destroyed again by Israeli soldiers.

*Wafa al Najjar, shot while returning to demolished family home roughly 800m from border.

*Mohammed Al Brim, shot February 17 by Israeli soldier while working on land over 500 m from border.

*farmers show injuries from Israeli soldier fire and how to crawl to safety when under fire. [photos: Fida Qishta]

*left: terrified farmer cowering from Israeli fire

*right: Leila Abu Dagga, fell down stairs trying to escape Israeli gunfire at her home roughly 500 m from border

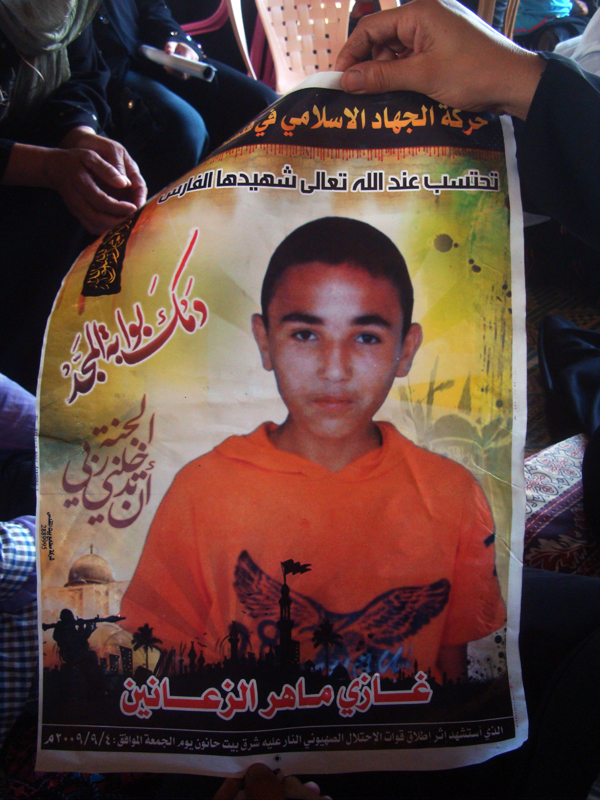

*left: Ghazi Zaneen, killed by Israeli soldiers while on family farmland.

*right [photo: farming under fire] farmer shot in spine with explosive bullet

*even the shallowest Israeli bulldozer ruts cause farmers great detours in order to avoid spilling their carts’ goods

*one of few working cisterns, Abu Taima land, southeastern Gaza (photo: Rada Daniell)

*Khoza’a destroyed cisterns

*Jaber Abu Rjila’s destroyed cistern, pump and chicken farm

*wheat crops set afire by Israeli-fired incendiary device, Johr ad Dik, May 2009

*irrigation piping, valuable and now expensive and/or non-existant in Gaza due to the years-long siege on Gaza. Farmers are desperately in need of piping, fertilizers, seeds, seedlings, replacement parts for farm equipment… These are all banned under the Israeli-led, internationally-complicit siege on Gaza.

related posts:

where is the buffer zone?

lost livelihoods

dignified beyond losses

cemetery casualties

bless his soul: Gaza Ramadan day 16

rising casualties in the buffer zone

buffer zone widow

Farmer, 4th Farmer Shot in 3 weeks

54 days

Rotting in the “Buffer Zone” or “The Shalom of Israel” [VIDEO]

Recovering dead body under Israeli fire (version with effects) [VIDEO]

farmers under fire [VIDEO]

lost in the buffer zone

the third hit her in the kneecap