In Gaza

It’s like spring and we’re visiting the Abu Taima region. The different Abu Taima brothers and cousins speak of their land, all in or near the Israeli-imposed “buffer zone” (officially 300m in which Palestinians cannot enter without fear of being shot, killed; but in reality a land-annexation which extends even up to nearly 2 km, driving farmers off their land and rendering land un-used…a waste of space in a Strip that has no space to waste).

Mohammed, the 14 year old son of one of the discouraged men, knows the land and its history. He tours us around, points out vacant plots where almond, fruit and olive trees once stood, and refers to Balfour and the days of the British occupation of Palestine.

He’s astute, and comes to the point of the buffer zone: “they want to drive us off the land, by any means possible,” he says of the long-held Zionist policies.

But he smiles, open, pleasant, and continues to re-visit their land.

“We used to come here every day, to work on the land, tend the trees, relax.”

He’s not the first I’ve heard reminisce about the beauty of the land pre-bulldozers. It was an area replete with trees, fertile, filled with life.

We walk past another puddle of rubble, and Mohammed explains it once housed a number of rabbits, one of several small initiatives of income generating, including raising chickens and sheep.

“This cistern was destroyed during the war,” he says pointing out a cement lined water cistern rendered useless. “When the F-16 bombed over there,” –points to a field with sparse crops re-growing –”some of the rubble from the building landed in the cistern, clogged it, destroyed the motor.”

What random bombings didn’t destroy, Israeli bulldozers finished off…all over the Strip.

Roughly 20 metres away, another useless cistern, this one plastic-lined. “We cannot build with cement, there is none thanks to the siege. But we line the pit with heavy plastic and it does fine as a cistern.”

Until the bulldozers fill in the pit with earth and rubble, tear the plastic.

In the case of this cistern, the small cement hut next to it, which once served as a kitchen and shade from the sun or shelter from winter cold, has been bulldozed, tumbling into the cistern, clogging it too.

“The whole point of these cisterns is to gather rain water,” Hamdan Abu Taima takes over. “Now we have to buy water from Khan Younis instead, if we want to work on our land.”

Their land troubles range from lack of water sources, to toxins from Israel’s chemical weapon useage, to toxins from the broken asbestos roves of felled houses and buildings… to rotting animal carcasses.

Their land troubles include the regular Israeli bulldozing of the land, the last Israeli war on Gaza’s extensive bombing throughout the Strip, and the daily threat from heavily-armed Israeli soldiers in military jeeps, “hummers” and in mechanized guard towers all along Gaza’s border with Israel.

“This is where Nabil was killed,” Mohammed says of a teenage relative. He points to the next field where a massive F-16 crater has been filled in. “Nabil wanted to see the crater. It was only the 2nd day of the war; we didn’t know about the zananas yet,” he says of the unmanned drones which were responsible for a hefty portion of the 1500 martyred in Israel’s massacre of Gaza.

He was heading to the crater with his brother Khalil when the zanana fired.

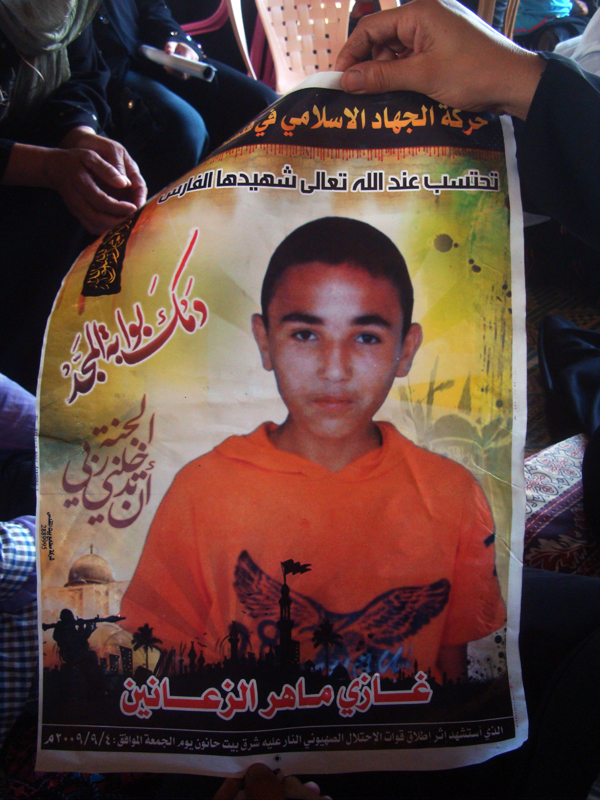

A photo of the martyred youth decorates the nearest pole to Abu Taima’s home back in the village.

Khalil was badly injured but thankfully has since recovered. Physically.

“64 dunams,” says Abdul Nasser Abu Taima. “64 dunams of hothouses were destroyed in the last war alone.”

He’s speaking of the Abu Taima land only.

“Shameful,” says Abu Taima. “This palm tree was tall, produced many dates.” The stump he gestures at disgustedly is less than a third of it’s original grandeur.

Hamdan Abu Taima keeps bees. “We had about 17 before the war. Now we’ve got 7. The rest were bulldozed. But anyway, there aren’t enough trees any more to feed the bees. We supplement with sugar. Years ago, when there were so many trees, the honey was so good, so pure.”

We sit in the shade of some of the young olive trees and watch Israeli jeeps patrol the border over 1km away. Even from this distance, the farmers’ fear is palpable in their wary glances. It’s all normal to them, yet they can’t help but worry. They’ve planted some sparse crops and hope these will make it to harvest season.

Leaving the graveyard of wells and land, we return via another dirt road to Abu Taima’s home. Mohammed keeps a running monologue, pointing out plot after plot of ravaged, arid, or vacated land.

“This was a potato patch. After it was bulldozed, they started to only grow wheat.”

“kullo roht, kullo roht, he says, a wizened young man.

“These cacti, they take 5 years to mature. We eat their fruits. But the Israelis bulldozed all along the roads.”

The next morning I return with ISM (international activists) to accompany Abu Taima and farmers to his land, to add fertilizer to the wheat we managed to plant last week.

As usual, we are given tea, coffee, and some treat before we set off: Abu Taima wouldn’t allow otherwise. One morning’s treat was freshly baked whole wheat flatbread. This morning’s treat is a cinnamon dusted fried flatbread, cooked over a baboor (the kerosene-lamp-converted-stoves used in Gaza when cooking gas is nonexistant).

We’ve worked about 20 minutes when the Israeli military jeeps come, as per norm.

Of one of the 3 parked jeeps, 3 Israeli soldiers step down, assume shooting stance…and the shots begin.

Closer, closer, till its less than 10 metres from us.

The standard Israeli military reply to today will be that the soldiers’ shooting was a “response to their threatened security.”

Or something along that line.

But we observe the soldiers take a break from their shots, pause casually, gun to the side…and resume shooting.

After 12 or so minutes of shooting nearer and nearer to us, the Israeli soldiers finally leave.

And the farmers, ever-accustomed to the drill, return slowly to the land, to finish the work they’ve begun and are completing in pieces.

Yarub.