by Radhika Sainath

25 November 2011 | Notes from Behind the Blockade

It all started with a simple question from Jabar, a Palestinian farmer from Faraheen, during Eid al-Adha, the festival of sacrifice.

“Is there an American eid (holiday) where you slaughter an animal?” he asked Nathan, a colleague here in Gaza, a few weeks ago.

Thanksgiving and turkeys came to mind.

And so, I found myself celebrating “Thanksgiving,” Gazan-style, this afternoon in the small, southern Gazan village.

Nathan painstakingly put together a variety of ingredients over the past couple of weeks to make a proper meal: turkey, baked beans, sweet potatoes, biscuits and chocolate chip cookies! We had to nix the stuffing, gravy was too difficult, and pie, out of the question.

After six weeks of falafel (delicious as it is), I was really looking forward to Nathan’s Midwestern cuisine. But would it all come together given Gaza’s regular power outages, Israel’s recent shooting at farmers in the area and the lack of key ingredients due to the siege?

We rose early to accompany farmers in Faraheen to their land within Israel’s 300 meter ”buffer zone” – or “kill zone” – as Palestinians here frequently call it.

The week had not been a good one, and I was concerned that our belated Thanksgiving would turn into Black Friday.

On Wednesday, the Israeli army had shot live ammunition in the air when our group went with farmers to the buffer zone in nearby Khuza’a.

The day before, the Israeli army had called the Palestinian Office of Coordination and told them that they “wanted to shoot” us and twenty Palestinians while we were in northern Gaza nonviolently protesting the Israeli occupation, the buffer zone, and 63 years of dispossession in the buffer zone. The Palestinian Authority frantically looked for the phone number of Saber Zanin, the organizer of the weekly Beit Hanoun protests and told him, “We are trying to ask the Israelis not to shoot you. They wanted to shoot you and kill you.”

And yesterday, 3 nautical miles of the coast of Gaza, an Israeli naval warship chased our small humanitarian boat, the Oliva, along with several Palestinian fishing boats, towards the shore for no apparent reason.

Today just couldn’t be good. Would our Gazan Thanksgiving look more like the original Thanksgiving — a symbol of land seizure, dispossession and ethnic cleansing — than the delicious turkey-filled version I was hoping for?

I rose early, gulped down a cup of sugary tea and dry floury date cookies that Jabar’s wife Layla made before heading out to the buffer zone. The sky cleared and I heard Israeli drones overhead.

On the way to the buffer zone, we met 26-year-old Yusef Abu Rjeela, the farmer who want was hoping to sow wheat on his land. We asked him what he wanted to do if the Israelis started shooting.

“Stay on the land,” he said. If the Israelis shot in the air, he didn’t want to run. And if they shot at us, well…

We continued onward, and my cell phone rang. It was Nathan. “I put the beans in the pressure cooker for 30 minutes and they’ve become bean soup!” he exclaimed. “Layla says I shouldn’t have soaked them and used the pressure cooker.”

“Stay calm,” I said. “Do you have more beans?” He did. We continued on our way.

Five of us foreigners donned our yellow vests, and accompanied Yusef and another farmer as one sowed wheat and the other plowed the land. The drones went away.

All seemed quiet on the eastern front.

An Israeli military tower stood in the distance. A white balloon equipped with an aerial surveillance camera flew overhead. The former farmland was dry and brown from years of Israeli bulldozing and tank traffic.

After a while, we made bets on when the Israelis would start shooting. It was 11:25 a.m., and I put in for 11:45 a.m., another person for 11:50 a.m. Hussein, a Palestinian university student who came with us, didn’t think the Israelis would shoot at all.

At noon, the farmers had finished and we all started to walk back to the village. Yusef explained to us the lawsuit his family had filed against the state of Israel for murdering his younger brother the day after Operation Cast Lead ended in January 2009. His father, who had witnessed the murder, had gone to Israel to testify.

As we left the buffer zone, I congratulated Hussein on being right about the shooting. Then we heard it — Israeli army gunfire in the distance. The time: 12:05.

We promptly head back to Jabar’s house in the village. There, Nathan was immersed in a whirlwind of preparation.

“Get the baking soda out of the bag!” he directed.

“You mean baking powder?” I asked him, looking the plastic bag he had brought from Gaza City.

“No, soda.” There was no baking soda. We were in for a biscuit disaster. Moreover, Layla and four of her five children were swirling around the kitchen, unsure of these strange American preparations.

Beans with sugar? In the oven? Nathan opened the ancient iron contraption, and held out a spoon for me. I stuck my tongue out and slurped up the brown deliciousness.

“Is it good?” asked Layla, suspiciously. “Is Nathan a good cook? Can you cook better?”

“Zacky ikthir,” I responded. Very tasty. “Not quite done,” I said to Nathan. “I can cook, but maybe Nathan is better than me,” I added to Layla. She didn’t seem convinced.

Nathan shooed everyone away, but we stayed in the kitchen, it was the warmest room in their small, cement block, metal sheet-roofed house. And, I was clearly the only one cut out for the role of taster. Layla turned to more important questions.

“You’re a lawyer, can you sue Israel for me?” she asked. “All our problems come from Israel. When I was 14, they shot me in the hip. Then they bulldozed our olive trees and took our land. What can we do?” I hadn’t realized that Layla’s limp stemmed from about 1980, when the Israeli army entered her school and shot her as she tried to help a wounded friend.

She turned away to take the turkey out of the pot. The oven wasn’t big enough for a whole bird, which was only sold in pre-cut pieces. All in all, it was a delicious lunch, and no one got shot. And that, is something to be thankful for.

Updated on November 30, 2011

25 November 2011 | Notes from Behind the Blockade

Layla and her daughters with the turkey in Faraheen (Photo: Radhika Sainath, Notes from Behind the Blockade) - Click here for more images

“Is there an American eid (holiday) where you slaughter an animal?” he asked Nathan, a colleague here in Gaza, a few weeks ago.

Thanksgiving and turkeys came to mind.

And so, I found myself celebrating “Thanksgiving,” Gazan-style, this afternoon in the small, southern Gazan village.

Nathan painstakingly put together a variety of ingredients over the past couple of weeks to make a proper meal: turkey, baked beans, sweet potatoes, biscuits and chocolate chip cookies! We had to nix the stuffing, gravy was too difficult, and pie, out of the question.

After six weeks of falafel (delicious as it is), I was really looking forward to Nathan’s Midwestern cuisine. But would it all come together given Gaza’s regular power outages, Israel’s recent shooting at farmers in the area and the lack of key ingredients due to the siege?

We rose early to accompany farmers in Faraheen to their land within Israel’s 300 meter ”buffer zone” – or “kill zone” – as Palestinians here frequently call it.

The week had not been a good one, and I was concerned that our belated Thanksgiving would turn into Black Friday.

On Wednesday, the Israeli army had shot live ammunition in the air when our group went with farmers to the buffer zone in nearby Khuza’a.

The day before, the Israeli army had called the Palestinian Office of Coordination and told them that they “wanted to shoot” us and twenty Palestinians while we were in northern Gaza nonviolently protesting the Israeli occupation, the buffer zone, and 63 years of dispossession in the buffer zone. The Palestinian Authority frantically looked for the phone number of Saber Zanin, the organizer of the weekly Beit Hanoun protests and told him, “We are trying to ask the Israelis not to shoot you. They wanted to shoot you and kill you.”

And yesterday, 3 nautical miles of the coast of Gaza, an Israeli naval warship chased our small humanitarian boat, the Oliva, along with several Palestinian fishing boats, towards the shore for no apparent reason.

Today just couldn’t be good. Would our Gazan Thanksgiving look more like the original Thanksgiving — a symbol of land seizure, dispossession and ethnic cleansing — than the delicious turkey-filled version I was hoping for?

I rose early, gulped down a cup of sugary tea and dry floury date cookies that Jabar’s wife Layla made before heading out to the buffer zone. The sky cleared and I heard Israeli drones overhead.

On the way to the buffer zone, we met 26-year-old Yusef Abu Rjeela, the farmer who want was hoping to sow wheat on his land. We asked him what he wanted to do if the Israelis started shooting.

“Stay on the land,” he said. If the Israelis shot in the air, he didn’t want to run. And if they shot at us, well…

We continued onward, and my cell phone rang. It was Nathan. “I put the beans in the pressure cooker for 30 minutes and they’ve become bean soup!” he exclaimed. “Layla says I shouldn’t have soaked them and used the pressure cooker.”

“Stay calm,” I said. “Do you have more beans?” He did. We continued on our way.

Five of us foreigners donned our yellow vests, and accompanied Yusef and another farmer as one sowed wheat and the other plowed the land. The drones went away.

All seemed quiet on the eastern front.

An Israeli military tower stood in the distance. A white balloon equipped with an aerial surveillance camera flew overhead. The former farmland was dry and brown from years of Israeli bulldozing and tank traffic.

After a while, we made bets on when the Israelis would start shooting. It was 11:25 a.m., and I put in for 11:45 a.m., another person for 11:50 a.m. Hussein, a Palestinian university student who came with us, didn’t think the Israelis would shoot at all.

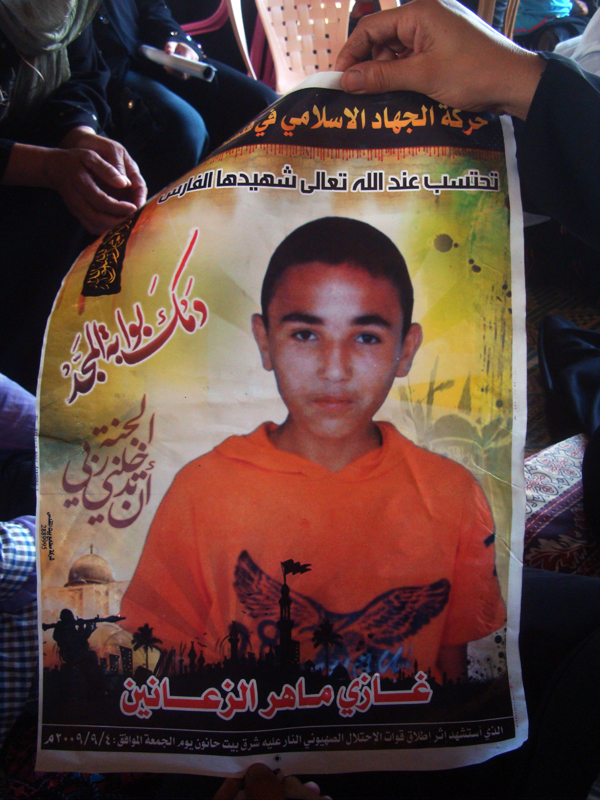

At noon, the farmers had finished and we all started to walk back to the village. Yusef explained to us the lawsuit his family had filed against the state of Israel for murdering his younger brother the day after Operation Cast Lead ended in January 2009. His father, who had witnessed the murder, had gone to Israel to testify.

As we left the buffer zone, I congratulated Hussein on being right about the shooting. Then we heard it — Israeli army gunfire in the distance. The time: 12:05.

We promptly head back to Jabar’s house in the village. There, Nathan was immersed in a whirlwind of preparation.

“Get the baking soda out of the bag!” he directed.

“You mean baking powder?” I asked him, looking the plastic bag he had brought from Gaza City.

“No, soda.” There was no baking soda. We were in for a biscuit disaster. Moreover, Layla and four of her five children were swirling around the kitchen, unsure of these strange American preparations.

Beans with sugar? In the oven? Nathan opened the ancient iron contraption, and held out a spoon for me. I stuck my tongue out and slurped up the brown deliciousness.

“Is it good?” asked Layla, suspiciously. “Is Nathan a good cook? Can you cook better?”

“Zacky ikthir,” I responded. Very tasty. “Not quite done,” I said to Nathan. “I can cook, but maybe Nathan is better than me,” I added to Layla. She didn’t seem convinced.

Nathan shooed everyone away, but we stayed in the kitchen, it was the warmest room in their small, cement block, metal sheet-roofed house. And, I was clearly the only one cut out for the role of taster. Layla turned to more important questions.

“You’re a lawyer, can you sue Israel for me?” she asked. “All our problems come from Israel. When I was 14, they shot me in the hip. Then they bulldozed our olive trees and took our land. What can we do?” I hadn’t realized that Layla’s limp stemmed from about 1980, when the Israeli army entered her school and shot her as she tried to help a wounded friend.

She turned away to take the turkey out of the pot. The oven wasn’t big enough for a whole bird, which was only sold in pre-cut pieces. All in all, it was a delicious lunch, and no one got shot. And that, is something to be thankful for.