In Gaza

“I had a chicken farm with 3,000 chickens. On the 300 dunams [1 dunam is 1000 square metres] of land I share with neighbours I had 300 olive trees, 130 dates, 200 lemons, 150 papayas, 500 guavas, 200 clementines. I had 50 dunams of wheat and another 50 of peas.

This was all destroyed, all but about 400 chickens. Destroyed before Israel even waged it’s 23 day massacre of Gaza in winter 2008/2009. The last of the chickens died in that attack.

My radish crops, which I’d planted where trees once stood, I had to plow under because they were poisoned by the phosphorous which rained down here.”

Down in Al Faraheen, the farming village east of Khan Younis, a visiting delegation wants to see life in the ‘buffer zone‘. We visit Jaber Abu Rjila whose daily life is a microcosm of many of the problems in Gaza:

-his land has been razed repeatedly by invading Israeli bulldozers;

-his house has been shot up by the Israeli soldiers powering the military dozers; his wife and children have been terrorized, trapped in their home while the invaders shot up and destroyed their livelihoods –one of his younger daughters is psychologically scarred from the experience, won’t eat, is consequently malnourished and nervous;

-their agricultural practices have been devastated by the Israeli massacre in winter 2008/2009, by prior Israeli invasions, by the all-encompassing Israeli-led but internationally-complicit siege on Gaza;

-their farmland, aside from being rendered off-limits by the Israeli-imposed ‘buffer zone’, has been poisoned by the chemical munitions rained upon them during the winter Israeli massacre;

-he has lost relatives and friends to the bullets of Israeli soldiers invading his community…

Their list is a long one, and Jaber is vocal.

We re-visit the May 1st, 2008 Israeli invasion which was the most catastrophic to their livelihood: in a day, their chicken farm, orchards of mature olive and fruit trees, and farm equipment were all destroyed by the Israeli bulldozers, tanks, and soldiers who overtook the region.

We re-visit the winter massacre, during which Faraheen residents evacuated their homes and returned to destruction. Jaber still has what he says is a white phosphorous shell. And has, with his dry sense of humour, fashioned a wind-chime out of spent Israeli ammunition casings.

We ask: how do you know the Israeli army fired chemicals on your land. He cites the crops he’s had to plow under for their poor growth; he points out a date tree that isn’t producing like it should [there are a few bunches of dates where there should be tens, he says].

As we leave, trying to keep to the delegation’s schedule, Jaber and Leila are non-surprisingly insistent we stay: for a meal, for the night… it is only 11 am.

In Khoza’a, another farming village a little further south along the border, we meet Iman An Najjar, one of the hundreds of residents subject to Israeli military terror during the massacre. Khoza’a became internationally known for the multiple atrocities which occurred by the invading Israeli soldiers: civilians were bombed in their homes, were shot while holding white flags, had to flee the Israeli bulldozers leveling home after home, and were subject to clouds of white phosphorous which burned to the bone, killing and scarring for life. The most intense period lasted from early morning to evening 13 January, after which a reported 14 Khoza’a residents were slain, 50 injured, and over 200 suffered gas inhalation. [see: Chaos in Khoza'a ]

*Iman an Najjar relates the horrors of the 13 January massacre.

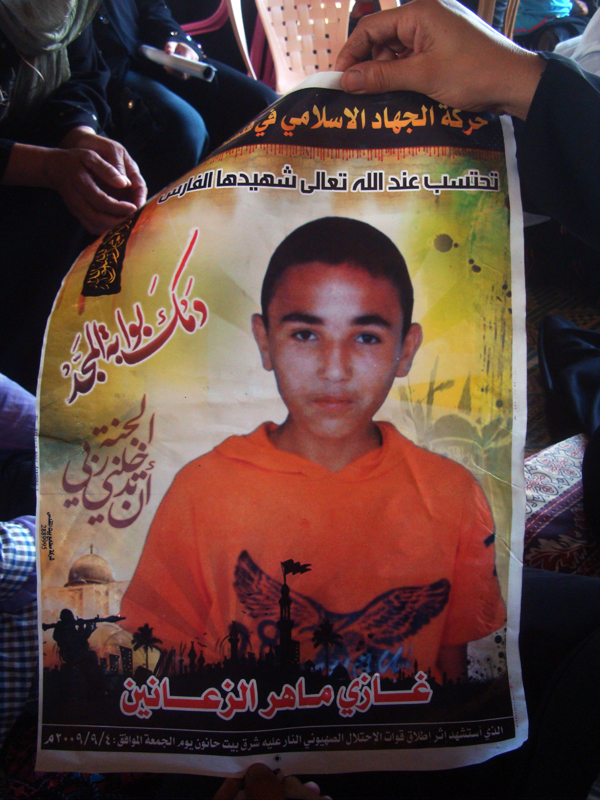

*boys from Khoza’a.

In Gaza, many feel that Eid, a time of joy for Muslims, is only really for children, as they can be temporarily distracted and made happy by the toys and holiday joy. But for many children, balloons and new clothes won’t even dent the psychological damage and trauma of their experience during the Israeli massacre.

Back in Gaza City in the early evening, the streets are now packed with shebab –the young men of Palestine. They tour arm in arm or in small groups, friends united, roaming and looking for something to do. They are joined by families, likewise streaming down the main street in Rimal area, many heading for the one park in the area, to sit, drink tea, and watch for friends. People are dressed in their best, many in new clothes, and walk proudly.

But that’s it, that’s all there is for them. Nothing special to enjoy, no means of celebrating with family or friends in the occupied West Bank, no means of holiday travel like people elsewhere in the world.