Gaza City, Gaza – Israel's warning came from the sky, as it often does in the Gaza Strip. But this time warplanes dropped neither bombs nor missiles on the impoverished Palestinian territory, but thousands of tiny leaflets warning Gaza's residents to keep away from the 30-mile-long border they share with Israel.

Stay at least 300 meters (1,000 feet) from the border, the May 25 pamphlets advised Palestinians, or risk being shot by Israeli Defense Forces (IDF).

Once a plush scene of rolling olive, citrus, and pomegranate groves, much of the border region is now just a barren landscape, marked only by the presence of IDF tanks, military watchtowers, and the occasional pop of gunfire.

Farmers and their families have been displaced, too afraid to return to their fields, while international humanitarian organizations are unable to make an assessment of the needs and damages of the area in the aftermath of the assault.

"We haven't been able to visit this area. No organization has," says Mohammed al-Shattali, project manager for the United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) in the Gaza Strip.

"The war increased the amount of land destroyed, particularly in the border areas, and the farmers can't replant anything because it's too dangerous," he says. "The Israeli soldiers, they shoot at everything – dogs, sheep. They are very tense."

An Israeli-imposed buffer zone in the already narrow enclave was established more than a decade ago to thwart attacks by Palestinian militants, who use the border areas to launch homemade rockets at Israeli towns or dig tunnels to carry out attacks against IDF troops stationed at the border.

But what was previously just a sliver of fortified land on the strip's northern and eastern perimeters now, in the aftermath of Israel's January offensive in the territory, swallows roughly 30 percent of Gaza's arable farmland, according to the FAO.

It stretches as deep as 1.25 miles inside Gaza's territory in the north and half a mile in the east, despite the 300-meter figure declared on the leaflets, the organization says. Gaza is just 25 miles long and slightly more than six miles wide.

Israel's rationale: prevent terrorism, future wars

The IDF Spokesperson's Unit officially declined to comment on actions taken in the buffer zone, as well as on whether or not warning leaflets had in fact been dropped.

But Shlomo Brom, an IDF veteran and senior research fellow at the Tel Aviv-based Institute for National Security Studies, says Israeli army policy in the buffer zone is perfectly reasonable given the frequency of attacks by Palestinian fighters.

According to IDF statistics, more than 7,000 rockets have been launched at Israel from the Gaza Strip since 2005. In 2006, Palestinian militants who dug a tunnel under the Israeli-Gazan border captured Israeli Cpl. Gilad Shalit, who has yet to be released.

"The buffer zone makes the digging of such tunnels much more complicated and much more difficult," says Brig. Gen. Brom (ret.). "And Israel established the zone mainly because Palestinian armed groups were attacking Israeli patrols with explosive charges on the Israeli side of the border."

Brom says stricter enforcement of the buffer zone in the wake of Israel's military assault is not aimed at making life more difficult for the people of Gaza, but to prevent them from suffering another similar attack in the future.

"The IDF is now more strict in maintaining this buffer zone because one of the reasons the recent military offensive was launched is because we allowed terrorist activities from Gaza to continue," says Brom. "If we are more strict and we don't allow the situation to deteriorate, then we can avoid a repeat of the last war. There is a smaller probability the fighting will escalate in Gaza."

Dwindling supplies of fresh food

Both Israel's January offensive and the newly expanded buffer zone have devastated Gaza's agricultural sector, the FAO says.

Officially aimed at weakening the power of the Islamist movement Hamas, whose charter calls for the destruction of Israel, the three-week military assault destroyed much of the strip's already dilapidated infrastructure, including wide swaths of agricultural land that are now part of the buffer zone.

The World Food Program (WFP) says the inability of Gaza's farmers to cultivate their land in the wake of the assault is depriving the territory's 1.5 million residents of an important source of otherwise scarce fresh food.

Already sparse after a 2-year economic siege, Gaza's local food markets face dwindling supplies of the parsley, spinach, chickpeas, dates, carrots, and pomegranates once grown on plots of land near the border.

Despite the buffer zone's disastrous effects on the local population, Amnesty International's head researcher for Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territories says Israel's expansion of it is not without merit.

"The movement westward of the danger zone, or Israel's buffer zone if you'd like, didn't just come out of the blue," Donatella Rovera says.

"Israeli actions are linked somewhat to the fact that on the Palestinian side, there are people who go to these areas simply to farm their land and there are people who go and do other things," she says. "And the latter are legitimate targets, because they are combatants."

But Ms. Rovera says Israel's further encroachment on Gaza's land is disproportionate to the threat involved, suggesting unmanned drones as a possible alternative method of surveillance.

'There has to be a way'

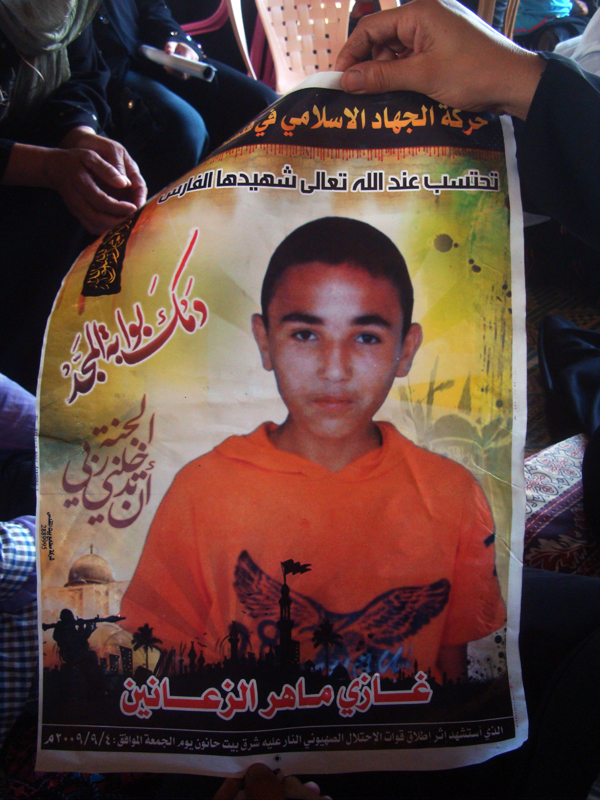

Since the operation ended on Jan. 18, 12 Palestinian civilians have been shot – three of them fatally – in areas within 3,000 feet of the border, according to human rights activists and medical officials here.

Nabeel al-Najjar, a farmer from the rural village of Khuzaa, 15 miles southeast of Gaza City, was shot in the hand on Jan. 23 when he returned to the rubble of his home less than a mile from the border.

"I came back to see if I could get a few things from my house, and they shot me," Mr. Najjar said. "How can I continue to live here knowing I am close enough for them to kill me whenever they want?"

In Jaher Al-Deek, a Bedouin farming village south of Gaza City, Omar Suliman has abandoned his decades-old olive grove, located a quarter mile from the Israeli border, for fear of being shot.

"When I was a kid, we used to be able to go to the border," Mr. Suliman says over the crackle of gunfire from a nearby Israeli observation post.

"We would joke with the Israeli soldiers and give them grapes from our field. They would give us chocolate," he says. "Now, they just shoot at us every day."

Without guarantees for their safety, Gaza's farmers are unlikely to return to the buffer zone in high numbers anytime soon, says the FAO's Mr. Shattali.

"The situation is very sensitive, for both sides," he acknowledges. "But there has to be a way people can cultivate their land without being killed."

Please wait ...

Please wait ...